The Come-Up:

One of the goals of this Crater’s Edges series is to examine the evolution of a band or artist through their peak, to see what they picked up over the course of their career that leads them to make their masterpiece and how they move on – or don’t move on – afterwards. Writing about electronic music narrows this down to its purest form. Electronic musicians aren’t superstars, their personal lives aren’t packaged as a narrative, and if they have the equipment, then they can bust out albums without even setting foot in a studio, making for less music-label drama. In a ton of electronic genres there aren’t lyrics. It becomes a pure exercise of identifying the sounds and examining how those evolved.

Autechre, over these three albums, show a very tangible evolution in their sound. Their first album, Incunabula, was a compilation of previously-released tracks that cast them as meditative ambient techno artists in the vein of Global Communication or Orbital. They were pretty good at this. Some ambient techno artists preferred to deploy vocal samples, but Autechre kept it strictly instrumental and let their synths carry the tracks alongside breezy breakbeats. Nobody regards Incunabula to be a classic, but standout tracks like “Bike” had an exploratory, pastoral vibe that showed promise. When you compare it to their later albums, it sounds downright cute.

Amber is Autechre’s first album that was meant to be an album, and the long-player format allows them to settle down and stretch out. Slower tempos and simpler melody lines abound. This is the closest that the band ever gets to straight-up ambient music. Having listened to it a lot to soundtrack my end-of-the-day readings and unwind, I can tell you it works well for that. These songs just don’t draw a lot of attention to themselves.

If you’re listening to it intently, you won’t find a lot of missteps, either – it’s a very consistent album even though there are clear standouts such as “Montreal,” a lost early Aphex Twin song if there ever was one, and “Slip,” which contains the album’s most intricate melody. That said, they all drag along far too much. Again, this isn’t a problem if you regard the album as utilitarian and are just looking for a quiet soundtrack to throw on while you do something else. But the songs don’t have enough detail packed into them to justify their extended lengths (only two songs clock in under six minutes).

But there are signs that a different path awaits for them. “Glitch,” true to its title, hums along on a distorted computer-modem sample, pinging in and out of the speakers like a living thing. It’s not quite accurate to say it’s the best song on the album, as Autechre are still invested in their ambient techno sound and spend more time exploring the limits of that. But it is the song that gets the most mileage out of the least input. It’s a clear sign of where Autechre’s true talents lie.

The Peak:

Tri repetae is a massive and satisfying moment of things clicking into place. The ambient techno sound is gone, and now Autechre are pioneers of what we all recognize today as Intelligent Dance Music (or IDM, since like most critics I hate the name and will avoid using it). Most of what substantively changes on Tri repetae are the drumbeats, which have gone from gentle waves pushing the song along into mechanistic locked grooves. We now have something less reminiscent of a trip through space than a trip through a brutal Industrial Age factory.

As for the sounds, well… when Autechre made “Glitch,” the sound of a glitchy tape was such a novelty in their catalogue that they named the song after it. But now that sound is the standard. I don’t know if Autechre had studied the work of noisy contemporaries Panasonic, but a punishingly minimal song like “Rotar,” which rhythmically punches your eardrums with analog blurts, shares undeniable sonic elements with them. And through it all, the uneasy bass tones provide invaluable color. The way they use those low tones on this album to keep the tracks engaging throughout reminds me of a jazz-fusion trumpet, if you can believe that.

For the first time Autechre sounded like the Autechre as we know them today, fearlessly diving into abstraction, minimalism, and harshness. Even the song titles reflect this; they weren’t quite the inscrutable keyboard-smashes we’re used to, but they had at least stopped being real words. They had discovered their palette, and were now free to paint on it.

The Comedown:

Chiastic Slide is little-remembered and little-loved, standing in between the twin triumphs of Tri repetae and LP5. In practice, Autechre discovered an entirely new sonic world of intricate glitch constructions and then regressed a bit. Chiastic Slide sounds more like a precedent, a building-up to their magnum opus than an antecedent to it. Its sound reaches for a synthesis of Amber and Tri repetae, and though its feet are still planted in the latter, you can still see why they chose to push their sound to one extreme.

Take the opener and album standout “Cipater”: it has the loud and minimalist drum programming of latter-day Autechre, but those drums are allowed to sputter and clash with a plaintive synth melody. It works very well, but in any other Autechre album the priorities would be reversed. The melodies would muster their forces and ultimately fall short, scattered around a brutalist drum loop. “Cichli” strikes a better balance with its curious, lightweight synthesized harps existing alongside, but never quite melding with, the glitch bursts. It’s the sound of an unfettered soul making its way through a terrifying labyrinth, blissfully unaware of the danger.

The result is that Chiastic Slide is their most lucid full-length, a democratic album that’s about as appealing as you’ll ever make glitch music. Even with the grinding drums in play it’s the cutesiest Autechre release since Incunabula. But it just doesn’t hold my attention the way their best ones do; the band doesn’t go full-bore on anything here, and as a result the tracks don’t have the bracingly hypnotic quality that keeps me thrilled over nine whole minutes, which Autechre songs tend to extend to. This sounds like they’re coloring outside the lines of what they’re best at. It’s still a tense, tight listen, but I just prefer Autechre acknowledging that aspect of their music and deciding to double down on it. That’s when the truly mind-melting stuff happens.

But can you blame them for trying? When an artist’s magnum opus is also the album where they find their sound, their unique niche, it’s natural to see where that sound can extend. They would dive down the hole of opaque brutalism on subsequent releases LP5 and Confield, but Chiastic Slide had to happen so they knew to do that in the first place.

The Verdict:

A toughie – both albums are skirting around the edges of the territory where Autechre would stake their claim as visionary electronic artists, dabbling in things that made them sound more like their peers. But they’re good for different reasons. Amber is a relaxing bed while Chiastic Slide is a jogging companion.

I’m going with Amber today. It works better in the utilitarian sense of putting it on to work to without taking too much of your attention, and in fact works better that way. Plus as a second album of ambient techno, it’s about as refined and well-judged as Autechre would get in that genre before throwing the whole thing out and coming up with something new.

Wednesday, September 27, 2017

Tuesday, September 19, 2017

The Crater's Edges #4: Brand New (Deja Entendu v. Daisy)

In the eight years since Daisy came out, we all seemed to realize how much Brand New meant. Publications everywhere – and I’m not just talking Alternative Press or Punknews.org, but supposedly high-minded ones like Pitchfork or Noisey – are rushing to acclaim Science Fiction because they know it’s the last chance they’ll have. Brand New are The Emo Band That Made It. They don’t have the cultural baggage of Fall Out Boy or their former rivals Taking Back Sunday.

My story with Brand New is just one of many, but over the course of their crossing over to the mainstream, I’m sure there are lots just like it. My first years of paying attention to music and engaging with new releases was spent on a small music forum. We liked what we liked there, which was mostly Pitchfork favorites but with some crossing over into other scenes. Roughly fifty regular posters participated there, of which three or four were legitimate punks –forming their own bands with friends, seeing shitty basement shows, following the incestuous scene with verve and attention. Those couple of folks never got us to really embrace Set Your Goals or Owen or whatever, but Brand New was a point of common interest. Jesse Lacey’s merry band started out being influenced by Their bands (Sunny Day Real Estate, Lifetime, Glassjaw) and into Our bands (Modest Mouse, Built to Spill, Pixies). They were a great equalizer.

Which is, in the end, due to the music. There was something special in Brand New’s music that caught the ears of people in two different scenes – even people like me, who wouldn’t even find out those scenes existed until years later. Something that encouraged their fans to explode with enthusiasm and share it with everyone they could, until finally it’s 2017 and Brand New are getting their due from everyone. The music did all that.

So let’s talk about it, finally, huh?

The Come-Up:

Brand New were already perfect for what they were on their debut album. Your Favorite Weapon is an ecstatic, tightly-wound collection of pop-punk songs. The band never lets up on its barrage of drop-tuned power chords or harmonized vocals and Jesse Lacey never stops being a flamboyant little shit both lyrically or vocally. But in the two years between their debut and Deja Entendu, Brand New first pulled the trick that would define them for the rest of their career: uprooting their sound and settling for something different that nonetheless sounds fully-formed and confident. Any other band who went from Your Favorite Weapon to Deja Entendu would need an album in-between to ease into that sound, to try things and fail forward. Not Brand New.

The main difference in sound is tempo. Their songs barreled forward with reckless intensity on their first album, but Deja Entendu is resolutely midtempo. The first proper song, “Sic Transit Gloria… Glory Fades” enters with a thumping, rubbery bassline pushing the song forward, and it would be an entirely alien sound on Your Favorite Weapon. That’s not to say that the band’s tools are entirely different – you’ve still got the energetic chorus, complete with screams – but they’re being bent towards other ends. These slower songs mean that the band has to lay down deeper grooves, and the instrumentalists step up to the plate: guitarist Vincent Accardi and bassist Garrett Tierney’s loping performance is vital to the success of “Jaws Theme Swimming,” and Brian Lane handles the frequent verse/chorus tempo changes on songs like “The Quiet Things That No One Ever Knows” and “Guernica” with apblomb. And they sound great. Mike Sapone, who produced all the band’s albums, gives Deja Entendu a reverbed, dreamy atmosphere while letting all the instruments stay clear and noticeable in the mix. The album doesn’t hit very hard, but that floaty sound, like they’re holding back, is no small reason why Brand New mesmerizes so many people.

But – and he would probably hate to hear this – Jesse Lacey continues to play the role of rock-star frontman here. Fortunately, he’s shifted his lyrical concerns from adolescent put-downs, revenge against exes, and histrionic bitching into something more self-aware. “Watch me cut myself wide open on this stage,” he sings on “I Will Play My Game Beneath the Spin Light.” He’s well aware of the power he commands as a popular musician (“Oh, I would kill for the Atlantic / But I am paid to make girls panic while I sing”) and spends the album alternately pumping himself up over it and lamenting how toxic the position is. “Okay I Believe You But My Tommy Gun Don’t” is a pitch-black comedy of curdling masculinity, Lacey proclaiming “These are the words you wish you wrote down / This is the way you wish your voice sounds / Handsome and smart / Oh, my heart’s the only muscle on my body that works harder than my heart.” But on “Me vs. Maradona vs. Elvis,” that same power curdles and numbs him: “I will lie awake / And lie for fun, and fake the way I hold you / Let you fall for every empty word I say.” It’s the most dead and hopeless he’s ever sounded on record… to date, at least.

“Me vs. Maradona vs. Elvis” is key to Deja Entendu. On the one hand, it’s the most beautiful melody the band has ever written, a terrific showcase of Lacey’s meticulous vocals. On the other hand, it’s where the band runs out of steam and shows the limits of this sound. Over and over on Deja Entendu (“I Will Play My Game Beneath the Spin Light,” “Okay I Believe You But My Tommy Gun Don’t,” “The Boy Who Blocked His Own Shot,”) the band has gone from acoustic strumming to full-band rocking to enliven proceedings, and on “Me vs. Maradona vs. Elvis,” a song that really didn’t need it, they pull the same trick again. It sounds obligatory, as if they have no enthusiasm for it. It takes them four measures of dead-eyed power-chord strumming before they can even muster the last chorus. It’s as if they just realized, “hey, we’re pretty good at this sound, but it isn’t really where our heart is at.” And the three songs after it don’t offer much to change that view: “Guernica” is a lot of energy in service of no real lyrical soul, “Good to Know That If I Need Attention All I Have to Do Is Die” rides a fake-out ending as interminable as its title for far too long, and “Play Crack the Sky” can only offer an overdone metaphor (this relationship… is like a sinking ship!) At least when they closed out Your Favorite Weapon with an acoustic song, “Soco Amaretto Lime,” it was filled with bitter humor and irony.

By the end Deja Entendu shows the need for growth – which is quite a thing for a band that had already grown a massive amount in such a short time. Sure, I’m not hot on the end of the album, but those first seven-and-a-half songs are great. They showed that they could change with the times and deliver a worthy follow-up, that they weren’t going away any time soon. Not enough people were paying attention to them, but they should have been.

The Peak:

I said that it sounded like Your Favorite Weapon and Deja Entendu should have had an album of intermediate development in between them, so great were the sonic changes. Well, that’s pretty much what happened in between Deja Entendu and the subsequent album. Fans leaked eight demos that Brand New had been workshopping for their third album to the internet. These demos, eight untitled tracks under the bootleg name Fight Off Your Demons and eventually released to the public under the name Leaked Demos 2006, were mostly pretty good. They featured heartbreaking acoustic tunes, songs that wouldn’t have sounded out-of-place on Deja Entendu, and experimentation with new instruments.

But the release of those demos is mostly seen as a good thing, as the band scrapped most of them and opted to start over, with a new batch of songs that nevertheless benefitted from the trial-and-error manpower that they had already put into changing up their sound. So when The Devil and God Are Raging Inside Me came out in 2006, Brand New had once again set their foot firmly into a new aesthetic. People responded – not as many people as should have been listening in the first place, but those who did heard something special.

Brand New, on their magnum opus, finally found a mode that they were supernaturally good at: discomfort. The quietLOUD dynamics were pushed to their extremes, desperate whispers giving way to piercing wails. Jesse Lacey ceded more lyrical control to Vincent Accardi, and together their words expressed a pitch-black existential despair. Mike Sapone outdid himself, sucking away the comfortable blanket of Deja Entendu in favor of letting the notes ring out and echo into what sounds like a gaping maw. Most importantly, the songs stopped being predictable: rather than uniformly starting midtempo and getting louder for the choruses, they squirmed, lunged, built up and collapsed.

It’s one of the best rock albums of the 2000s, one with an outsize (and arguably still-growing) reputation that far outstrips the modest success it had at the time. But it was one without an obvious follow-up, and though Brand New would keep being Brand New, when they finally returned, not everybody was happy with the results.

The Comedown:

Daisy sounds like an album from a younger band. Maybe that’s why people had a hard time wrapping their heads around it: Brand New chose to push one element of their sound to its extreme rather than play around with the shades of grey they had introduced on their last album. That kind of move is normally associated with artists who haven’t come into their own yet. The Devil and God Are Raging Inside Me was self-consciously a masterpiece, an hour-long album with a variety of moods and a surprising wealth of approaches. Daisy, on the other hand, is Brand New’s shortest album at just over forty minutes. Compared to what came before, it’s lean, mean, and unforgiving.

The desire to push their sound to the extreme is clear from the opener “Vices,” which starts with a crackly recording of an opera singer before smashing through the walls with bludgeoning noise and Jesse Lacey’s hellish screams, so loud and mixed so far into the red that the recording clips with the effort of trying to contain it all. If anyone ever got the idea that Lacey was flaunting his good looks and poetic faculties to pose as a rock star, Daisy obliterates the notion. He’s not some brooding Byronesque hero here, but an avatar of despair – moreover, one completely willing to sit in the background. The climaxes of “You Stole” and “Bought A Bride” come not with the traditional Brand New shouted chorus but with white-hot guitar leads from Vincent Accardi.

The band’s love of quietLOUD dynamics persists here, but they’ve found new ways to be loud. Mike Sapone’s favorite trick here is to bury Lacey’s vocals behind distortion, while letting the band overtake him, most notably in “Daisy” and “Noro.” These songs blow out the drums and bass, leaving Lacey unmoored in an increasingly turbulent sea. The hypnotic “Bed” is the moment when the band learns the value of repetition, growing more intense with every chant of the harmonized “Laid her on the bed” chorus even though there’s no singular moment of explosion. It feels like they rejected the studio as a crutch in favor of working on their ability as a band. The Devil and God Are Raging Inside Me was immaculately produced, but Daisy blasts the whole thing to the extreme so that the band have nothing to rely on but themselves. Everything on here is guitar, bass, and drums – no pianos, no overdubs, not even an acoustic guitar.

For all that Daisy gets rejected by Brand New fans, I think it was vital to their legacy. The influences here are clear, but they lean towards 90s noise rock – The Jesus Lizard, Fugazi, Jawbox, Slint. Those are names that mainstream publications have a lot easier time swallowing. Most of them had dismissed Brand New by 2003 (at the latest) and to hear them deliver an album that owed so much to that "respectable" strain of rock music made it clear that there was something more to Brand New. Which led them to work backwards and rediscover The Devil and God Are Raging Inside Me. So Brand New diehards waited for a new album because they wanted to know if Daisy was a one-off and the band would return to their “real” sound. New fans waited because they wanted to see how they built on Daisy to create a new sound. And they all waited. And waited. And the band’s legend grew exponentially, until…

Well, I already had a big thing about this at the beginning of the review.

The Verdict:

I’m an unabashed Daisy apologist, sorry. I think it’s their second-best album behind The Devil and God Are Raging Inside Me. I think it’s wild that they managed to make two albums that are so good for such different reasons. For the third time in a row, Brand New stepped into a new skin and inhabited it well. With the release of Science Fiction, it’s much easier to see how it fits into their evolution – as a mapping-out of how far they could push the abrasive discomfort of their sound. When they returned, eight years later, to something more expansive and Devil and God-ish, they sounded more confident than ever in who they were. Daisy is responsible for that.

But more importantly, it’s just a great noise-rock album. The highlights are doled out liberally, unlike the supremely frontloaded Deja Entendu, and the band turns in fantastic performances. I’m calling it, this week, for the comedown album.

My story with Brand New is just one of many, but over the course of their crossing over to the mainstream, I’m sure there are lots just like it. My first years of paying attention to music and engaging with new releases was spent on a small music forum. We liked what we liked there, which was mostly Pitchfork favorites but with some crossing over into other scenes. Roughly fifty regular posters participated there, of which three or four were legitimate punks –forming their own bands with friends, seeing shitty basement shows, following the incestuous scene with verve and attention. Those couple of folks never got us to really embrace Set Your Goals or Owen or whatever, but Brand New was a point of common interest. Jesse Lacey’s merry band started out being influenced by Their bands (Sunny Day Real Estate, Lifetime, Glassjaw) and into Our bands (Modest Mouse, Built to Spill, Pixies). They were a great equalizer.

Which is, in the end, due to the music. There was something special in Brand New’s music that caught the ears of people in two different scenes – even people like me, who wouldn’t even find out those scenes existed until years later. Something that encouraged their fans to explode with enthusiasm and share it with everyone they could, until finally it’s 2017 and Brand New are getting their due from everyone. The music did all that.

So let’s talk about it, finally, huh?

The Come-Up:

Brand New were already perfect for what they were on their debut album. Your Favorite Weapon is an ecstatic, tightly-wound collection of pop-punk songs. The band never lets up on its barrage of drop-tuned power chords or harmonized vocals and Jesse Lacey never stops being a flamboyant little shit both lyrically or vocally. But in the two years between their debut and Deja Entendu, Brand New first pulled the trick that would define them for the rest of their career: uprooting their sound and settling for something different that nonetheless sounds fully-formed and confident. Any other band who went from Your Favorite Weapon to Deja Entendu would need an album in-between to ease into that sound, to try things and fail forward. Not Brand New.

The main difference in sound is tempo. Their songs barreled forward with reckless intensity on their first album, but Deja Entendu is resolutely midtempo. The first proper song, “Sic Transit Gloria… Glory Fades” enters with a thumping, rubbery bassline pushing the song forward, and it would be an entirely alien sound on Your Favorite Weapon. That’s not to say that the band’s tools are entirely different – you’ve still got the energetic chorus, complete with screams – but they’re being bent towards other ends. These slower songs mean that the band has to lay down deeper grooves, and the instrumentalists step up to the plate: guitarist Vincent Accardi and bassist Garrett Tierney’s loping performance is vital to the success of “Jaws Theme Swimming,” and Brian Lane handles the frequent verse/chorus tempo changes on songs like “The Quiet Things That No One Ever Knows” and “Guernica” with apblomb. And they sound great. Mike Sapone, who produced all the band’s albums, gives Deja Entendu a reverbed, dreamy atmosphere while letting all the instruments stay clear and noticeable in the mix. The album doesn’t hit very hard, but that floaty sound, like they’re holding back, is no small reason why Brand New mesmerizes so many people.

But – and he would probably hate to hear this – Jesse Lacey continues to play the role of rock-star frontman here. Fortunately, he’s shifted his lyrical concerns from adolescent put-downs, revenge against exes, and histrionic bitching into something more self-aware. “Watch me cut myself wide open on this stage,” he sings on “I Will Play My Game Beneath the Spin Light.” He’s well aware of the power he commands as a popular musician (“Oh, I would kill for the Atlantic / But I am paid to make girls panic while I sing”) and spends the album alternately pumping himself up over it and lamenting how toxic the position is. “Okay I Believe You But My Tommy Gun Don’t” is a pitch-black comedy of curdling masculinity, Lacey proclaiming “These are the words you wish you wrote down / This is the way you wish your voice sounds / Handsome and smart / Oh, my heart’s the only muscle on my body that works harder than my heart.” But on “Me vs. Maradona vs. Elvis,” that same power curdles and numbs him: “I will lie awake / And lie for fun, and fake the way I hold you / Let you fall for every empty word I say.” It’s the most dead and hopeless he’s ever sounded on record… to date, at least.

“Me vs. Maradona vs. Elvis” is key to Deja Entendu. On the one hand, it’s the most beautiful melody the band has ever written, a terrific showcase of Lacey’s meticulous vocals. On the other hand, it’s where the band runs out of steam and shows the limits of this sound. Over and over on Deja Entendu (“I Will Play My Game Beneath the Spin Light,” “Okay I Believe You But My Tommy Gun Don’t,” “The Boy Who Blocked His Own Shot,”) the band has gone from acoustic strumming to full-band rocking to enliven proceedings, and on “Me vs. Maradona vs. Elvis,” a song that really didn’t need it, they pull the same trick again. It sounds obligatory, as if they have no enthusiasm for it. It takes them four measures of dead-eyed power-chord strumming before they can even muster the last chorus. It’s as if they just realized, “hey, we’re pretty good at this sound, but it isn’t really where our heart is at.” And the three songs after it don’t offer much to change that view: “Guernica” is a lot of energy in service of no real lyrical soul, “Good to Know That If I Need Attention All I Have to Do Is Die” rides a fake-out ending as interminable as its title for far too long, and “Play Crack the Sky” can only offer an overdone metaphor (this relationship… is like a sinking ship!) At least when they closed out Your Favorite Weapon with an acoustic song, “Soco Amaretto Lime,” it was filled with bitter humor and irony.

By the end Deja Entendu shows the need for growth – which is quite a thing for a band that had already grown a massive amount in such a short time. Sure, I’m not hot on the end of the album, but those first seven-and-a-half songs are great. They showed that they could change with the times and deliver a worthy follow-up, that they weren’t going away any time soon. Not enough people were paying attention to them, but they should have been.

The Peak:

I said that it sounded like Your Favorite Weapon and Deja Entendu should have had an album of intermediate development in between them, so great were the sonic changes. Well, that’s pretty much what happened in between Deja Entendu and the subsequent album. Fans leaked eight demos that Brand New had been workshopping for their third album to the internet. These demos, eight untitled tracks under the bootleg name Fight Off Your Demons and eventually released to the public under the name Leaked Demos 2006, were mostly pretty good. They featured heartbreaking acoustic tunes, songs that wouldn’t have sounded out-of-place on Deja Entendu, and experimentation with new instruments.

But the release of those demos is mostly seen as a good thing, as the band scrapped most of them and opted to start over, with a new batch of songs that nevertheless benefitted from the trial-and-error manpower that they had already put into changing up their sound. So when The Devil and God Are Raging Inside Me came out in 2006, Brand New had once again set their foot firmly into a new aesthetic. People responded – not as many people as should have been listening in the first place, but those who did heard something special.

Brand New, on their magnum opus, finally found a mode that they were supernaturally good at: discomfort. The quietLOUD dynamics were pushed to their extremes, desperate whispers giving way to piercing wails. Jesse Lacey ceded more lyrical control to Vincent Accardi, and together their words expressed a pitch-black existential despair. Mike Sapone outdid himself, sucking away the comfortable blanket of Deja Entendu in favor of letting the notes ring out and echo into what sounds like a gaping maw. Most importantly, the songs stopped being predictable: rather than uniformly starting midtempo and getting louder for the choruses, they squirmed, lunged, built up and collapsed.

It’s one of the best rock albums of the 2000s, one with an outsize (and arguably still-growing) reputation that far outstrips the modest success it had at the time. But it was one without an obvious follow-up, and though Brand New would keep being Brand New, when they finally returned, not everybody was happy with the results.

The Comedown:

Daisy sounds like an album from a younger band. Maybe that’s why people had a hard time wrapping their heads around it: Brand New chose to push one element of their sound to its extreme rather than play around with the shades of grey they had introduced on their last album. That kind of move is normally associated with artists who haven’t come into their own yet. The Devil and God Are Raging Inside Me was self-consciously a masterpiece, an hour-long album with a variety of moods and a surprising wealth of approaches. Daisy, on the other hand, is Brand New’s shortest album at just over forty minutes. Compared to what came before, it’s lean, mean, and unforgiving.

The desire to push their sound to the extreme is clear from the opener “Vices,” which starts with a crackly recording of an opera singer before smashing through the walls with bludgeoning noise and Jesse Lacey’s hellish screams, so loud and mixed so far into the red that the recording clips with the effort of trying to contain it all. If anyone ever got the idea that Lacey was flaunting his good looks and poetic faculties to pose as a rock star, Daisy obliterates the notion. He’s not some brooding Byronesque hero here, but an avatar of despair – moreover, one completely willing to sit in the background. The climaxes of “You Stole” and “Bought A Bride” come not with the traditional Brand New shouted chorus but with white-hot guitar leads from Vincent Accardi.

The band’s love of quietLOUD dynamics persists here, but they’ve found new ways to be loud. Mike Sapone’s favorite trick here is to bury Lacey’s vocals behind distortion, while letting the band overtake him, most notably in “Daisy” and “Noro.” These songs blow out the drums and bass, leaving Lacey unmoored in an increasingly turbulent sea. The hypnotic “Bed” is the moment when the band learns the value of repetition, growing more intense with every chant of the harmonized “Laid her on the bed” chorus even though there’s no singular moment of explosion. It feels like they rejected the studio as a crutch in favor of working on their ability as a band. The Devil and God Are Raging Inside Me was immaculately produced, but Daisy blasts the whole thing to the extreme so that the band have nothing to rely on but themselves. Everything on here is guitar, bass, and drums – no pianos, no overdubs, not even an acoustic guitar.

For all that Daisy gets rejected by Brand New fans, I think it was vital to their legacy. The influences here are clear, but they lean towards 90s noise rock – The Jesus Lizard, Fugazi, Jawbox, Slint. Those are names that mainstream publications have a lot easier time swallowing. Most of them had dismissed Brand New by 2003 (at the latest) and to hear them deliver an album that owed so much to that "respectable" strain of rock music made it clear that there was something more to Brand New. Which led them to work backwards and rediscover The Devil and God Are Raging Inside Me. So Brand New diehards waited for a new album because they wanted to know if Daisy was a one-off and the band would return to their “real” sound. New fans waited because they wanted to see how they built on Daisy to create a new sound. And they all waited. And waited. And the band’s legend grew exponentially, until…

Well, I already had a big thing about this at the beginning of the review.

The Verdict:

I’m an unabashed Daisy apologist, sorry. I think it’s their second-best album behind The Devil and God Are Raging Inside Me. I think it’s wild that they managed to make two albums that are so good for such different reasons. For the third time in a row, Brand New stepped into a new skin and inhabited it well. With the release of Science Fiction, it’s much easier to see how it fits into their evolution – as a mapping-out of how far they could push the abrasive discomfort of their sound. When they returned, eight years later, to something more expansive and Devil and God-ish, they sounded more confident than ever in who they were. Daisy is responsible for that.

But more importantly, it’s just a great noise-rock album. The highlights are doled out liberally, unlike the supremely frontloaded Deja Entendu, and the band turns in fantastic performances. I’m calling it, this week, for the comedown album.

Thursday, September 14, 2017

Review: Kirin J. Callinan - Bravado

For the first minute or two, Kirin J. Callinan’s sophomore album sounds like it might be a reasonable follow-up to Embracism, which is one of the more underrated albums of 2013. For his debut, Callinan meshed art pop and dark electro-industrial music together and gave it an unmistakable garnish: his yowling vocals. Callinan stammers and roars on his songs, blurting out non-sequitirs and repeating garbled lines with a ferocity that recalls fellow Australian wild-man Nick Cave. His lyrics match that violent intimacy, resplendent with male sexual energy and insecurity.

“My Moment,” the first song on Bravado, seems to trace the same path, with a ping-ponging synth line and unsettling atmospheric touches as Callinan drawls in his sleazy baritone. The song lumbers to life like an animal waking up. But when it finally explodes, about two-and-a-half minutes in, it’s not with squealing dissonance or full-band rocking like you’d get on Embracism: it’s with a Europop beat drop. It sounds like something PC Music would put out! In one moment, it obliterates the idea that Callinan would continue or refine the sound of Embracism; instead he’s taken a hard left, picked up a sense of humor, and become an utter troll.

That’s certainly how I found out about him, just a few days ago. A clip from the music video of “Big Enough,” one of the singles from Bravado, is getting passed around Tumblr right now. In it, we roam through shots of the Australian landscape as a woman whistles a plaintive melody, before panning up to the sky and seeing… a giant phantasm of a man (Australian hard rocker Jimmy Barnes) dressed in cowboy garb screaming over the empty plains. Please, I implore you to watch that whole video, because if you’re anything like me, you will feel an indescribable joy at the absurdity of it. It doesn’t even matter whether you know it’s not serious – the video is such a perfect encapsulation of the kitschy Eurovision aesthetic that it transcends needing to be a joke or not.

And that’s the modus operandi of Bravado – it tackles and defamiliarizes many different genres, but Callinan’s quirks override them all in ways that are just slightly uncomfortable and unfitting. He reminds me of Perfume Genius in the way his songs seem to slough over, not quite fitting the boxes he makes for them. The album’s lead single “S.A.D.” (“Song About Drugs”) juxtaposes the anthemic 80s synthpop production with lyrics about getting “a lungful of dope smoke” and being “wrapped up in plastic.” But the music goes further, complimenting every line with a squeamish pitch-shifted harmony vocal and letting Callinan indulge in spoken-word sections. Even the fist-in-the-air chorus constantly throws you off-balance by modulating the key up and down every other line. Often this sloppy discomfort expresses itself in the lyrics: “Down 2 Hang” carries itself on a series of increasingly disturbing metaphors for how “she’s down to hang.” First “like gliders in the sky… or sneakers on a wire” but then like “an asphyxiated man with a belt in a van, his dick in his hand / Like Jesus, she is down to hang.” Right after that, “Living Each Day” encourages listeners to “live each day like it’s your last one,” but Callinan’s version of doing that means that he must “shrug off the urge to systematically kill.”

It’s all funny, of course, but it would be moot if Callinan didn’t bring some good songs to the table. If this was just an album of genre parodies, it wouldn’t be worth much more than a new Lonely Island album. “Living Each Day” lopes around with a bouncy bassline and dead-simple guitar hook. The dance tracks like “My Moment” and “Big Enough” may be silly, but they’re also ebullient and likeable.

Over the first five gobsmackingly weird and funny songs on Bravado, Callinan rewrites your brain so much that it sounds mystifying and unfitting when he starts taking himself seriously. The second half of the album is, by and large, straightforward sophisti-pop songs. There’s hardly a trace of humor in songs like “Family Home,” a touching tune about childhood friends and growing up in difficult circumstances. The only trace of the first half’s energy is “This Whole Town,” which has the EDM dance stylings but very little of the humor. Granted, the closing track “Bravado” manages to transcend all that – it’s a genuinely beautiful confessional little synthpop song. Taken as a single and music video alongside the other music videos from this album (“S.A.D.,” “Living Each Day,” “Big Enough”) it obliquely passes comment on those genre parodies – “After all this time / It was all bravado.” I suspect I’ll be replaying and loving this one more than any of the other songs on the album in the coming months. It would be such a touching end to the album… if only Callinan hadn’t intentionally decided to be touching halfway through with all those other songs.

What you get on Bravado, then, is one half of two different records sutured together. The first half is a head-expanding cavalcade of delightfully trashy/disturbing satire, while the second half is an 80s-inspired sophisti-pop record. The problem is that the first half commits to such a dizzying aesthetic extremism that, without any tip of the hand to show why these two opposites go together, the actually-pretty-good second half sounds dull and out-of-place. I still recommend the first half to anyone with an interest in the gonzo, cheesy, or ill-advised. On those songs, Callinan confidently steps forward with every bad idea he can muster. It’s a shame that he can’t commit to those bad ideas for a whole album.

Tuesday, September 12, 2017

The Crater's Edges #3: Carole King (Writer v. Music)

The Come-Up:

Technically Writer is Carole King’s debut album, but that’s misleading description. There’s no sense in which King is starting out or developing here: by 1970 she was already a seasoned industry professional. With or without a soon-to-be-breakout solo career she would have already amassed an impressive collection of hits for other artists: The Shirelles’ “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow,” Little Eva’s “The Loco-Motion,” (nowadays better known under Grand Funk Railroad), The Crystals’ “He Hit Me (It Felt Like A Kiss)” and Aretha Franklin’s “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” most notable among them. King-Goffin is one of the classic 60s songwriting teams alongside Holland-Dozier-Holland and Greenwich-Berry-Spector.

Even the title Writer foregrounds King’s experience as a craftswoman first and foremost. It’s a canny play to commercial concerns: you’ll like this because you already know Carole King, even if you don’t know her! And the music largely backs that up, because these twelve songs all share rock-solid construction and melodic sense. Pretty piano figures and (especially) driving bass figures by Charles Larkey round out the songs and ensure that there’s always something going on within the standard pop structures. King has a supple voice that catches the emotional content of these songs without allowing that to drag them down. Interestingly for a pop-oriented songwriter, she does particularly well with the more country-leaning songs such as “To Love” and “Sweet Sweetheart.” Now that’s a career turn that could have been rewarding and interesting.

But for all that Writer’s bet-hedging is a reasonable commercial decision, it doesn’t do the album any favors as a listening experience. These songs are all credited to Carole King and Gerry Goffin, who had divorced a year earlier. I haven’t done the research and tracked down the origins of every single one of these tunes, but at least three of them were big singles for other artists, so I think it’s safe to assume that this album consists of King excavating her back catalogue for songs to cover. Goffin-King penned a lot of different songs for a range of different artists in many genres, and that variety is on display here – you’ve got rockier numbers like “Spaceship Races” alongside adult-contemporary piano ballads such as “Child of Mine” and the aforementioned country tunes. While King’s songwriting sense does a great job of holding these songs together, the piecemeal nature of Writer can’t help but be felt sometimes. It feels less genre-spanning than genre-inchoate.

Whether that’s an issue of label pressure or just a mixed call on King’s part I can’t say, but it just brings this down from a very-good album to a very-good collection of songs. But that more than clears the bar for a singer-songwriter finally stepping out and making her own statement. Listen to Writer to find some hidden gems or just hear what King brings to her own songs that other artists don’t or couldn’t.

The Peak:

I’ve got no clue what word-of-mouth forces existed in 1971 to make Tapestry one of the best-selling albums in history, especially because Writer kind of sunk on release. But I’m going to suggest at least one cause: it was a clear step up in quality. I’m not saying Tapestry soars leaps and bounds over her debut, but with more original songs and more forceful production, the latter album establishes Carole King’s distinctive voice with authority and grace.

I mean, this is one of those absurdly stacked albums that could double as a greatest hits: King still brings back some of her old hits to cover, but this time she gives us her own versions of “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow” and “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman,” two of her all-time classics. This is also the album with “It’s Too Late” / “I Feel the Earth Move,” a double A-side that stuck around on the charts ridiculously high for a ridiculously long time. Oh, and King’s version of “You’ve Got a Friend,” which became a major hit for James Taylor. That’s already five songs out of a twelve-song album that conquered the world. That the rest hold together better than any two given songs from Writer (most of these songs were, after all, written for the album) means a sophomore record with higher highs and higher lows. I still don’t think it’s personally as good as some of the other peaks of 70s singer-songwriterdom like Blue or Rumours, but it has a broad appeal and emotional levelheadedness that those records don’t.

The Comedown:

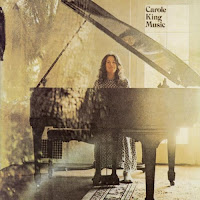

Carole King had been richly rewarded by going in a more rocking direction with Tapestry (I mean, that album’s not going to blow anyone’s ears out, but it was at least louder and with more active, noticeable drumming) so it’s a surprise that Music is mostly a smoothening and softening of her sound. The warmth and brightness of the album cover really bleeds through to the music here, and King sounds more assured than ever.

Musically the album relies more on the band than ever before – most of what makes Music different is the percussion work of conga-and-bongo-player extraordinaire Bobbye Hall, plus James Taylor’s acoustic guitar accompaniments. Taylor had played guitar on all of King’s albums up to this point, but his contributions here are the most pronounced and complex, intertwining with King’s stately piano figures in ways that always surprise and delight.

The songs themselves lean more toward low-key, sometimes even jazzy. There aren’t any lyrical stunners like “Child of Mine” nor are there any world-beating singles – even “Sweet Seasons,” the big hit from the album, coasts by with genial good feeling and no pressing need to make a statement. Sure, Music isn’t trying too hard, but after delivering a huge smash album and locking down a great studio band who are audibly having joy working together, King sounds happy to be working in her element and letting the music flow.

And that’s a significant change from where she had been before - Writer was a bit scattershot in approach if not in quality, whereas Tapestry, monumental as it is, feels weighed down by its big hits. Music is the most tight and consistent of these three albums. It feels like she’d made it over a hill – from songwriter who dealt in three-minute statements and pop hits to a singer-songwriter who could allow herself to stretch out and enjoy herself over forty minutes. King was right to title this one Music, because nothing else in her career has so clearly communicated the joy of making music and being surrounded by it. What a joy to hear!

The Verdict:

To be honest, I’d heard neither of these albums before I started writing this post; Sonic Youth and OutKast, I was familiar with, but not Carole King. Music, though, surprised me, and is an album I can see throwing on as a standard feel-good low-intensity listen. This week the advantage goes to the comedown album.

Technically Writer is Carole King’s debut album, but that’s misleading description. There’s no sense in which King is starting out or developing here: by 1970 she was already a seasoned industry professional. With or without a soon-to-be-breakout solo career she would have already amassed an impressive collection of hits for other artists: The Shirelles’ “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow,” Little Eva’s “The Loco-Motion,” (nowadays better known under Grand Funk Railroad), The Crystals’ “He Hit Me (It Felt Like A Kiss)” and Aretha Franklin’s “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” most notable among them. King-Goffin is one of the classic 60s songwriting teams alongside Holland-Dozier-Holland and Greenwich-Berry-Spector.

Even the title Writer foregrounds King’s experience as a craftswoman first and foremost. It’s a canny play to commercial concerns: you’ll like this because you already know Carole King, even if you don’t know her! And the music largely backs that up, because these twelve songs all share rock-solid construction and melodic sense. Pretty piano figures and (especially) driving bass figures by Charles Larkey round out the songs and ensure that there’s always something going on within the standard pop structures. King has a supple voice that catches the emotional content of these songs without allowing that to drag them down. Interestingly for a pop-oriented songwriter, she does particularly well with the more country-leaning songs such as “To Love” and “Sweet Sweetheart.” Now that’s a career turn that could have been rewarding and interesting.

But for all that Writer’s bet-hedging is a reasonable commercial decision, it doesn’t do the album any favors as a listening experience. These songs are all credited to Carole King and Gerry Goffin, who had divorced a year earlier. I haven’t done the research and tracked down the origins of every single one of these tunes, but at least three of them were big singles for other artists, so I think it’s safe to assume that this album consists of King excavating her back catalogue for songs to cover. Goffin-King penned a lot of different songs for a range of different artists in many genres, and that variety is on display here – you’ve got rockier numbers like “Spaceship Races” alongside adult-contemporary piano ballads such as “Child of Mine” and the aforementioned country tunes. While King’s songwriting sense does a great job of holding these songs together, the piecemeal nature of Writer can’t help but be felt sometimes. It feels less genre-spanning than genre-inchoate.

Whether that’s an issue of label pressure or just a mixed call on King’s part I can’t say, but it just brings this down from a very-good album to a very-good collection of songs. But that more than clears the bar for a singer-songwriter finally stepping out and making her own statement. Listen to Writer to find some hidden gems or just hear what King brings to her own songs that other artists don’t or couldn’t.

The Peak:

I’ve got no clue what word-of-mouth forces existed in 1971 to make Tapestry one of the best-selling albums in history, especially because Writer kind of sunk on release. But I’m going to suggest at least one cause: it was a clear step up in quality. I’m not saying Tapestry soars leaps and bounds over her debut, but with more original songs and more forceful production, the latter album establishes Carole King’s distinctive voice with authority and grace.

I mean, this is one of those absurdly stacked albums that could double as a greatest hits: King still brings back some of her old hits to cover, but this time she gives us her own versions of “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow” and “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman,” two of her all-time classics. This is also the album with “It’s Too Late” / “I Feel the Earth Move,” a double A-side that stuck around on the charts ridiculously high for a ridiculously long time. Oh, and King’s version of “You’ve Got a Friend,” which became a major hit for James Taylor. That’s already five songs out of a twelve-song album that conquered the world. That the rest hold together better than any two given songs from Writer (most of these songs were, after all, written for the album) means a sophomore record with higher highs and higher lows. I still don’t think it’s personally as good as some of the other peaks of 70s singer-songwriterdom like Blue or Rumours, but it has a broad appeal and emotional levelheadedness that those records don’t.

The Comedown:

Carole King had been richly rewarded by going in a more rocking direction with Tapestry (I mean, that album’s not going to blow anyone’s ears out, but it was at least louder and with more active, noticeable drumming) so it’s a surprise that Music is mostly a smoothening and softening of her sound. The warmth and brightness of the album cover really bleeds through to the music here, and King sounds more assured than ever.

Musically the album relies more on the band than ever before – most of what makes Music different is the percussion work of conga-and-bongo-player extraordinaire Bobbye Hall, plus James Taylor’s acoustic guitar accompaniments. Taylor had played guitar on all of King’s albums up to this point, but his contributions here are the most pronounced and complex, intertwining with King’s stately piano figures in ways that always surprise and delight.

The songs themselves lean more toward low-key, sometimes even jazzy. There aren’t any lyrical stunners like “Child of Mine” nor are there any world-beating singles – even “Sweet Seasons,” the big hit from the album, coasts by with genial good feeling and no pressing need to make a statement. Sure, Music isn’t trying too hard, but after delivering a huge smash album and locking down a great studio band who are audibly having joy working together, King sounds happy to be working in her element and letting the music flow.

And that’s a significant change from where she had been before - Writer was a bit scattershot in approach if not in quality, whereas Tapestry, monumental as it is, feels weighed down by its big hits. Music is the most tight and consistent of these three albums. It feels like she’d made it over a hill – from songwriter who dealt in three-minute statements and pop hits to a singer-songwriter who could allow herself to stretch out and enjoy herself over forty minutes. King was right to title this one Music, because nothing else in her career has so clearly communicated the joy of making music and being surrounded by it. What a joy to hear!

The Verdict:

To be honest, I’d heard neither of these albums before I started writing this post; Sonic Youth and OutKast, I was familiar with, but not Carole King. Music, though, surprised me, and is an album I can see throwing on as a standard feel-good low-intensity listen. This week the advantage goes to the comedown album.

Tuesday, September 5, 2017

The Crater's Edges #2: OutKast (Aquemini v. Speakerboxxx / The Love Below

The Come-Up:

OutKast ascended to pop stardom, then superstardom, then finally myth. It seems inevitable now, but in 1998 their next move wasn’t so obvious. Southernplayalisticcadillacmuzik was an instant Southern rap classic, an astonishing feat for two kids just out of high school, and rather than repeat their debut they transcended it with ATLiens. This was an album of rare vision – OutKast’s Southern scene prided itself on drug and gun talk - a down-to-earth realism. But these guys were down-to-Mars. Big Boi and Dre (soon to rename himself Andre 3000) positioned themselves as cosmic pimps, talented wordsmiths observing the ills of the world from an extraterrestrial perspective. They refused to sample old records and opted to create something fresh – in Big Boi’s words, “If it’s an old school jam, leave it to the old. We wanna have our own school of music.”

Most rap groups would bottom out after making two albums back-to-back of such staggering quality. Not OutKast – Aquemini might find them crashing back to Earth, but they don’t lose an ounce of their creativity. The result is OutKast’s best album, and I don’t care that I’m giving away the result of this week’s judgment call by saying that. It’s that important.

For Aquemini, the duo holed up in their studio with a bunch of professional musicians, jamming on musical ideas and crafting beats organically. From the jump, “Return of the ‘G’” offers a deeper, more seismic groove than anything OutKast or hip-hop had ever given us. You can get lost in just the bass playing on the title track. The grounding in musicianship and interplay yields thrilling results in the songcraft, too – I’ll never forget the first time I heard “Rosa Parks” break down into a harmonica-driven country hoedown. There’s a lot of living people playing the instruments on Aquemini, with deep and simmering influences from funk, soul and R&B. A comparison to the neo-soul scene of the late ‘90s feels obvious – and oh, would you look at that, Andre 3000 had just started dating the visionary musician and neo-soul fixture Erykah Badu!

But no neo-soul record had rappers of OutKast’s caliber on it. Now fully imbued with the alien soul that they first channeled on their journey to the stars, Boi and Dre command these songs. They rap with dumbfounding skill, sounding equally comfortable weaving intricate narratives as spitting freewheeling dope nonsense (see “Skew It on the Bar-B,” which is basically just the duo and Raekwon trying to one-up each other in the booth, competing for the hottest flow).

And when it seemed appropriate, OutKast simply abandoned hip-hop altogether. My favorite song on the album, and one of the greatest songs of the ‘90s, is “SpottieOttieDopaliscious,” which conjures up a swampy, romantic groove so intoxicating that time stretches out, the world outside your headphones fades, and all the remains is that fucking incredible horn hook and the luxurious spoken-word intonations of Boi and Dre. If there’s a complaint I can lodge against Aquemini, it’s that the epic funk journeys at the end of the album can be draining. But maybe the real problem with them is that they can’t live up to the standard set by “SpottieOttieDopaliscious.”

The result is a massive album, in every way. It has nooks and crannies to get lost in, a visionary sprawl, and a natural gravitas. I have a copy of it on vinyl (one of the few hip-hop vinyls I own, unfortunately) and its massive, singular aura seems to suck all the air out of the space around it. To listen to Aquemini is to be lost in a strange, funky new universe.

The Peak:

With all other worlds conquered, OutKast only had to cross over to the mainstream, and Stankonia did that. The duo and their Dungeon Family production crew returned to looped digital beats, but kept the wild and freewheeling genre mix in play, also adding in electronic, dance and pop influences. Stankonia sounded much more accessible on the surface – “So Fresh, So Clean” was a sizable hit and “Ms. Jackson” a massive one. But even a casual listen to the album revealed that it was just as sprawling, unwieldy, and uncompromising as Aquemini. Lead single “B.O.B.” sunk on release, probably because it was too much – lightning-quick verses over a frenetic beat, complete with guitar and turntable solos and a hype-you-up choral epilogue. But the song’s stature has grown and multiplied a thousand times since its release and now critics recognize it as one of the greatest songs of the decade. It didn’t sound like OutKast had caught up to the mainstream, or even that the mainstream had caught up to OutKast. Rather, the two met halfway for an album that launched them into the public eye while they were still at their most creative.

It’s also, full disclosure, not an album I like much. Sure, the singles are all bangers, and there are some good album cuts (“Gasoline Dreams” and “Humble Mumble” are my choices) but five or six songs out of a twenty-four-song album, replete with interludes and skits, isn’t enough for me. I can’t help but ding Stankonia for sounding unfocused and overlong. This might have been a problem for Aquemini too, but there OutKast consistently brought the excellent songs, and those aren’t here.

But I can remove my glasses of subjectivity to acknowledge that maybe I just haven’t listened to it at the right time or in the right frame of mind. Lots of other people love this album. It’s one of the most acclaimed of the 2000s. One day, maybe…

The Comedown:

Speakerboxxx / The Love Below emerged out of separate solo projects that Big Boi and Andre had coincidentally been working on at the same time. Critics had noted the temperamental differences between the two rappers as far back as Aquemini, but releasing a double album comprised of two separate solo albums seemed to be the breaking point. Paradoxically, it was also the duo’s popular peak. Selling Stankonia – an ambitious political rap epic – to the mainstream was one feat, but managing to go diamond off a double album full of Miami bass, Southern crunk, P-Funk, showtunes, R&B, jazz, and electro-pop is dumbfounding. The planet that OutKast made with Speakerboxxx / The Love Below had such a massive gravity that concerns about its instability were temporarily put on hold while the entire world got down to “Hey Ya!”

I’m tempted to do what nobody has done before and try to review Speakerboxxx / The Love Below as one consistent thing, a unified statement from OutKast that just so happens to almost never have the two members on the same track. But it would be foolish. Big Boi and Andre 3000 were at very different points in their lives in 2003, and it shows. Instead I’ll flip the script in a smaller way and review The Love Below first.

Either Erykah Badu had Andre reeling for three years straight or he had a series of smaller relationships that didn’t work out in the interim; either way, The Love Below is laser-focused on the topic of love and all that entails: romance and separation, sex and sexuality, gender and gender roles. Andre plays every kind of character here, from confident lothario to heartbroken bachelor, one minute fully in the spring of love and the next denouncing an evil woman. It’s as if Andre is desperately inhabiting every kind of persona he can think of so that he can triangulate the reason for the deep and aching pain inside his own soul. Behind every lyric and every situation lies the same question: “Why didn’t it work out?” The tragedy of The Love Below is that he never finds an answer – the album-ending “A Life in the Day of Benjamin Andre” has him recounting his life’s story, but only up to the present day. “You give it all your time because that’s all you can think about – and that’s as far as I got.” He can’t imagine a future for himself even after all that soul-searching.

Musically he sounds equally lost. It’s not like the elements on The Love Below don’t fit together – Prince pulled all these musical elements (plus a few more) into a cohesive whole in the 80s, and Andre 3000 is as charismatic a performer as Prince ever was. But the songs themselves are just so aimless. Too many of them descend into a mess of studio experimentation, spoken word, and dull repetition. It’s a 78-minute opus that should be at least twenty shorter. This album is where Andre got his reputation as an unfocused, scattershot dreamer who couldn’t pull it together enough to make a full-length statement.

Which is a shame, because on the occasions he does pull it together, it’s as though he’s reached deep into the veins of the universe, pulled them out, and showed them to us. Fourteen years later, “Hey Ya!” remains the iconic pop song of the 2000s. The moment on the album where “She Lives in My Lap” ends its interminable fade-out, only for Andre to shout “1-2-3!” and bust out the most tragic, catchy, singular tune of his career is a moment where the world is righted. To follow that up with “Roses” is almost unfair. “Roses” is a jaw-dropping testament to Andre’s charisma – he manages to make a top five hit out of the chorus “I know you think your shit don’t stink / but lean a lil’ bit closer, see / roses really smell like poo-poo,” and extends a line in the second verse so absurdly far that the music drops out and it becomes a dark murder fantasy, while making it sound totally natural and even funny, all so that he can find a rhyme for the word “bitch” – and in doing so validates the whole project. The Love Below could’ve been so good with an editor, but we have these two shining singles and a scattered assortment of other good bits. It’s hard to get too mad at a man tearing himself apart, no matter how uneven the results.

Speakerboxxx, Big Boi’s half of the project, is even easier to like. Three increasingly wild solo albums later, we can dispense with the fantasy that Big Boi is as traditional and grounded as we all pretended he was. He just happens to have a sound that intersected well with the sound of mainstream hip-hop in 2003. He also has a sense of how to compact and do justice to his good ideas instead of letting them get away from him. “GhettoMusick,” the album’s opening salvo, covers a lot of ground – by the time Big Boi starts rapping, we’ve already gone through a blistering chorus and mellow interlude section – but he keeps it moving, swapping out the numerous parts whenever one threatens to get boring and putting a lid on it just short of four minutes in. “GhettoMusick” begins an eight-song run of more-or-less flawless music. These songs sometimes let their choruses go on too long, but it’s hardly a problem, because they are in fact wonderful choruses, and when they snap back to Big Boi rapping – rapid-fire, complex, so caught up in its own message that he doesn’t care if you don’t get it at first – it’s bracing and thrilling.

Amid the flurry of rapping that Big Boi busts out, one song sticks out to me: “The Rooster.” Here, he talks about trying to be a father to his oldest son (“Round two, a single parent, what is Big to do? Throw a party? Not hardly, I’m trying to stay up outta that womb”) and even describes trying to change his child’s diapers. The spectacle of a respected Southern rapper talking about his son peeing on him speaks of a different relationship to, well, relationships than Andre has. Big Boi was by this time married to Sherlita Patton (who he’s still married to! Yay!) and the sense of maturity and stability permeates Speakerboxxx. Big Boi here is a guy who knows what he wants and is utterly at peace with his place as a rapper, father, and celebrity. He even puts his son Bamboo on an interlude, egging him on to drop a freestyle. You can hear the paternal affection and genuine care that he gives his son, who manages to crack him up just as much as fluster him.

Far be it for me to chalk up the differences between these two deeply different rappers (who were nonetheless born to make music together) up to the state of their love lives, but especially with Andre, the topic invites itself. The standard critical line on Speakerboxxx / The Love Below is that Speakerboxxx is the better album while The Love Below is at least an admirable effort redeemed by two world-conquering singles. Put together it’s a big, messy, triumphant package that captures the summer of 2003 like few other albums do.

The Verdict:

Well – I already gave it away. It’s Aquemini, the massive statement coming from two rappers who were distinct yet vibing on the same wavelength. But I really have to emphasize that as a front-to-back experience, Speakerboxxx is just a joy, certainly the album you’d put on to have a good time. Aquemini, though, cannot be topped. I declare the come-up album the winner this week.

OutKast ascended to pop stardom, then superstardom, then finally myth. It seems inevitable now, but in 1998 their next move wasn’t so obvious. Southernplayalisticcadillacmuzik was an instant Southern rap classic, an astonishing feat for two kids just out of high school, and rather than repeat their debut they transcended it with ATLiens. This was an album of rare vision – OutKast’s Southern scene prided itself on drug and gun talk - a down-to-earth realism. But these guys were down-to-Mars. Big Boi and Dre (soon to rename himself Andre 3000) positioned themselves as cosmic pimps, talented wordsmiths observing the ills of the world from an extraterrestrial perspective. They refused to sample old records and opted to create something fresh – in Big Boi’s words, “If it’s an old school jam, leave it to the old. We wanna have our own school of music.”

Most rap groups would bottom out after making two albums back-to-back of such staggering quality. Not OutKast – Aquemini might find them crashing back to Earth, but they don’t lose an ounce of their creativity. The result is OutKast’s best album, and I don’t care that I’m giving away the result of this week’s judgment call by saying that. It’s that important.

For Aquemini, the duo holed up in their studio with a bunch of professional musicians, jamming on musical ideas and crafting beats organically. From the jump, “Return of the ‘G’” offers a deeper, more seismic groove than anything OutKast or hip-hop had ever given us. You can get lost in just the bass playing on the title track. The grounding in musicianship and interplay yields thrilling results in the songcraft, too – I’ll never forget the first time I heard “Rosa Parks” break down into a harmonica-driven country hoedown. There’s a lot of living people playing the instruments on Aquemini, with deep and simmering influences from funk, soul and R&B. A comparison to the neo-soul scene of the late ‘90s feels obvious – and oh, would you look at that, Andre 3000 had just started dating the visionary musician and neo-soul fixture Erykah Badu!

But no neo-soul record had rappers of OutKast’s caliber on it. Now fully imbued with the alien soul that they first channeled on their journey to the stars, Boi and Dre command these songs. They rap with dumbfounding skill, sounding equally comfortable weaving intricate narratives as spitting freewheeling dope nonsense (see “Skew It on the Bar-B,” which is basically just the duo and Raekwon trying to one-up each other in the booth, competing for the hottest flow).

And when it seemed appropriate, OutKast simply abandoned hip-hop altogether. My favorite song on the album, and one of the greatest songs of the ‘90s, is “SpottieOttieDopaliscious,” which conjures up a swampy, romantic groove so intoxicating that time stretches out, the world outside your headphones fades, and all the remains is that fucking incredible horn hook and the luxurious spoken-word intonations of Boi and Dre. If there’s a complaint I can lodge against Aquemini, it’s that the epic funk journeys at the end of the album can be draining. But maybe the real problem with them is that they can’t live up to the standard set by “SpottieOttieDopaliscious.”

The result is a massive album, in every way. It has nooks and crannies to get lost in, a visionary sprawl, and a natural gravitas. I have a copy of it on vinyl (one of the few hip-hop vinyls I own, unfortunately) and its massive, singular aura seems to suck all the air out of the space around it. To listen to Aquemini is to be lost in a strange, funky new universe.

The Peak:

With all other worlds conquered, OutKast only had to cross over to the mainstream, and Stankonia did that. The duo and their Dungeon Family production crew returned to looped digital beats, but kept the wild and freewheeling genre mix in play, also adding in electronic, dance and pop influences. Stankonia sounded much more accessible on the surface – “So Fresh, So Clean” was a sizable hit and “Ms. Jackson” a massive one. But even a casual listen to the album revealed that it was just as sprawling, unwieldy, and uncompromising as Aquemini. Lead single “B.O.B.” sunk on release, probably because it was too much – lightning-quick verses over a frenetic beat, complete with guitar and turntable solos and a hype-you-up choral epilogue. But the song’s stature has grown and multiplied a thousand times since its release and now critics recognize it as one of the greatest songs of the decade. It didn’t sound like OutKast had caught up to the mainstream, or even that the mainstream had caught up to OutKast. Rather, the two met halfway for an album that launched them into the public eye while they were still at their most creative.

It’s also, full disclosure, not an album I like much. Sure, the singles are all bangers, and there are some good album cuts (“Gasoline Dreams” and “Humble Mumble” are my choices) but five or six songs out of a twenty-four-song album, replete with interludes and skits, isn’t enough for me. I can’t help but ding Stankonia for sounding unfocused and overlong. This might have been a problem for Aquemini too, but there OutKast consistently brought the excellent songs, and those aren’t here.

But I can remove my glasses of subjectivity to acknowledge that maybe I just haven’t listened to it at the right time or in the right frame of mind. Lots of other people love this album. It’s one of the most acclaimed of the 2000s. One day, maybe…

The Comedown:

Speakerboxxx / The Love Below emerged out of separate solo projects that Big Boi and Andre had coincidentally been working on at the same time. Critics had noted the temperamental differences between the two rappers as far back as Aquemini, but releasing a double album comprised of two separate solo albums seemed to be the breaking point. Paradoxically, it was also the duo’s popular peak. Selling Stankonia – an ambitious political rap epic – to the mainstream was one feat, but managing to go diamond off a double album full of Miami bass, Southern crunk, P-Funk, showtunes, R&B, jazz, and electro-pop is dumbfounding. The planet that OutKast made with Speakerboxxx / The Love Below had such a massive gravity that concerns about its instability were temporarily put on hold while the entire world got down to “Hey Ya!”

I’m tempted to do what nobody has done before and try to review Speakerboxxx / The Love Below as one consistent thing, a unified statement from OutKast that just so happens to almost never have the two members on the same track. But it would be foolish. Big Boi and Andre 3000 were at very different points in their lives in 2003, and it shows. Instead I’ll flip the script in a smaller way and review The Love Below first.

Either Erykah Badu had Andre reeling for three years straight or he had a series of smaller relationships that didn’t work out in the interim; either way, The Love Below is laser-focused on the topic of love and all that entails: romance and separation, sex and sexuality, gender and gender roles. Andre plays every kind of character here, from confident lothario to heartbroken bachelor, one minute fully in the spring of love and the next denouncing an evil woman. It’s as if Andre is desperately inhabiting every kind of persona he can think of so that he can triangulate the reason for the deep and aching pain inside his own soul. Behind every lyric and every situation lies the same question: “Why didn’t it work out?” The tragedy of The Love Below is that he never finds an answer – the album-ending “A Life in the Day of Benjamin Andre” has him recounting his life’s story, but only up to the present day. “You give it all your time because that’s all you can think about – and that’s as far as I got.” He can’t imagine a future for himself even after all that soul-searching.

Musically he sounds equally lost. It’s not like the elements on The Love Below don’t fit together – Prince pulled all these musical elements (plus a few more) into a cohesive whole in the 80s, and Andre 3000 is as charismatic a performer as Prince ever was. But the songs themselves are just so aimless. Too many of them descend into a mess of studio experimentation, spoken word, and dull repetition. It’s a 78-minute opus that should be at least twenty shorter. This album is where Andre got his reputation as an unfocused, scattershot dreamer who couldn’t pull it together enough to make a full-length statement.

Which is a shame, because on the occasions he does pull it together, it’s as though he’s reached deep into the veins of the universe, pulled them out, and showed them to us. Fourteen years later, “Hey Ya!” remains the iconic pop song of the 2000s. The moment on the album where “She Lives in My Lap” ends its interminable fade-out, only for Andre to shout “1-2-3!” and bust out the most tragic, catchy, singular tune of his career is a moment where the world is righted. To follow that up with “Roses” is almost unfair. “Roses” is a jaw-dropping testament to Andre’s charisma – he manages to make a top five hit out of the chorus “I know you think your shit don’t stink / but lean a lil’ bit closer, see / roses really smell like poo-poo,” and extends a line in the second verse so absurdly far that the music drops out and it becomes a dark murder fantasy, while making it sound totally natural and even funny, all so that he can find a rhyme for the word “bitch” – and in doing so validates the whole project. The Love Below could’ve been so good with an editor, but we have these two shining singles and a scattered assortment of other good bits. It’s hard to get too mad at a man tearing himself apart, no matter how uneven the results.

Speakerboxxx, Big Boi’s half of the project, is even easier to like. Three increasingly wild solo albums later, we can dispense with the fantasy that Big Boi is as traditional and grounded as we all pretended he was. He just happens to have a sound that intersected well with the sound of mainstream hip-hop in 2003. He also has a sense of how to compact and do justice to his good ideas instead of letting them get away from him. “GhettoMusick,” the album’s opening salvo, covers a lot of ground – by the time Big Boi starts rapping, we’ve already gone through a blistering chorus and mellow interlude section – but he keeps it moving, swapping out the numerous parts whenever one threatens to get boring and putting a lid on it just short of four minutes in. “GhettoMusick” begins an eight-song run of more-or-less flawless music. These songs sometimes let their choruses go on too long, but it’s hardly a problem, because they are in fact wonderful choruses, and when they snap back to Big Boi rapping – rapid-fire, complex, so caught up in its own message that he doesn’t care if you don’t get it at first – it’s bracing and thrilling.

Amid the flurry of rapping that Big Boi busts out, one song sticks out to me: “The Rooster.” Here, he talks about trying to be a father to his oldest son (“Round two, a single parent, what is Big to do? Throw a party? Not hardly, I’m trying to stay up outta that womb”) and even describes trying to change his child’s diapers. The spectacle of a respected Southern rapper talking about his son peeing on him speaks of a different relationship to, well, relationships than Andre has. Big Boi was by this time married to Sherlita Patton (who he’s still married to! Yay!) and the sense of maturity and stability permeates Speakerboxxx. Big Boi here is a guy who knows what he wants and is utterly at peace with his place as a rapper, father, and celebrity. He even puts his son Bamboo on an interlude, egging him on to drop a freestyle. You can hear the paternal affection and genuine care that he gives his son, who manages to crack him up just as much as fluster him.

Far be it for me to chalk up the differences between these two deeply different rappers (who were nonetheless born to make music together) up to the state of their love lives, but especially with Andre, the topic invites itself. The standard critical line on Speakerboxxx / The Love Below is that Speakerboxxx is the better album while The Love Below is at least an admirable effort redeemed by two world-conquering singles. Put together it’s a big, messy, triumphant package that captures the summer of 2003 like few other albums do.

The Verdict:

Well – I already gave it away. It’s Aquemini, the massive statement coming from two rappers who were distinct yet vibing on the same wavelength. But I really have to emphasize that as a front-to-back experience, Speakerboxxx is just a joy, certainly the album you’d put on to have a good time. Aquemini, though, cannot be topped. I declare the come-up album the winner this week.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)